The 1975 U.S. Women’s Pan American team. Carolyn Bush Roddy is the third from the left (between Coach Cathy Rush and Lusia Harris) in the back row. USA Basketball photo.

When Carolyn Bush Roddy got the call telling her she’d made it into the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame earlier this year, she’d just gone into the local Walmart in Knoxville. She was unable to move or say anything as Danielle Donehew, the executive director of the Women’s Basketball Coaches Association, gave her the good news. When she hung up, she couldn’t remember what she’d gone into Walmart to buy.

“So I went out to my car and just boo-hoo’d like a baby,” she recalls. “Then I went back inside and got what I’d come for. I drove home real slow….I don’t remember how I got home.”

Bush Roddy has been around the game of women’s basketball for more than 50 years. She can cite a connection to every single person who either played, coached, or officiated their way into the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame in its first 15 years of operation (except of course for Senda Berenson, who invented the game in 1892). Finally, she’ll be joining the greats of the women’s game when she’s inducted this coming June as part of the hall’s 21st class.

“My basketball career has been like a gigantic puzzle. Every piece has taken time to fit in where it needs to be,” she told me last week in a phone interview. “The hall of fame is the piece that’s finally found its place in my puzzle.”

Indeed, Bush Roddy has been part of many of the changes in women’s basketball in the last 50 years. She started out as a stationary guard in the old divided-court days at Roanne High School in Kingston, TN in 1966. “I was really spastic, and I could not walk and chew gum at the same time,” she says. “However, Coach (Freddie Paul) Wilson saw something in me and kept working to help me get better.”

She moved to stationary forward her sophomore year and, at 6-2 and 145 pounds, began dominating the action. She says she owes Coach Wilson a huge debt of gratitude for helping her develop not only her skills but also her passion for the game and the discipline to achieve her goals.

As an example, she cites the rough start to her freshman year in high school. She had 4 F’s, 1 C, and 2 D’s at the end of the first marking period. After the grades came out, Coach Wilson made her sit in the gym and watch the team practice while she did her homework. Every 30 minutes, he would tap her on the shoulder and ask if she wanted to play. When she answered yes, he’d tell her she couldn’t yet. This went on, she says, for two solid weeks.

“He was testing me to see how much I wanted to play,” she explains. “The next semester I had 4 A’s, 2 B’s and 1 C….All you have to do to get me to do something is tell me I can’t do it.”

Bush Roddy went on to earn MVP honors in 12 different tournaments her senior year, and played in the East & West All-Star Game, held at Stokley Center on the University of Tennessee at Knoxville campus in 1971.

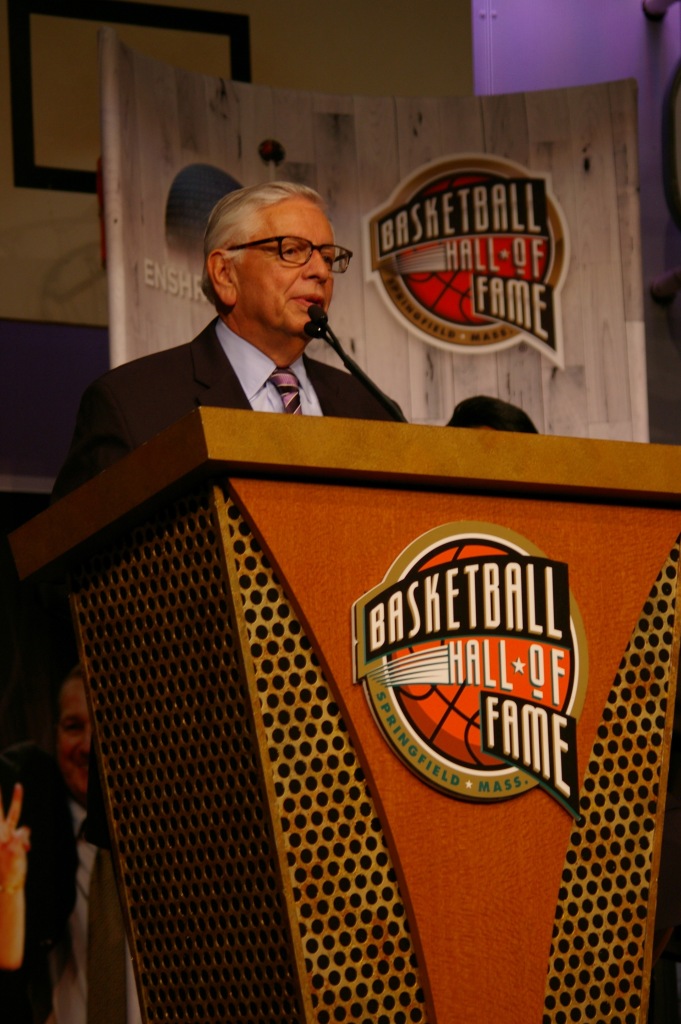

Bush Roddy is interviewed for a local station after the news of her induction in the WBHOF. Randy Ellis photo

Options for playing basketball after high school were improving around the country, but for a “country bumpkin” who didn’t want to stray too far from home, Hiwassee Junior College in nearby Madisonville, TN, which had switched to the five-player, full-court game, made sense.

“I’d always played with guys growing up,” she says. “I loved the five-player game.”

Her team made it to the national junior college tournament in both 1972 and 1973, which was held in Enid, Oklahoma. There, legendary coach Harley Redin of Wayland Baptist College took notice of Bush Roddy and recruited her to finish out her college career with the Flying Queens.

Wayland Baptist became known as much for flying the team to its games around the country as it did for its 131-game winning streak in the late 1950s. Bush Roddy says she grew to enjoy the plane rides, but you wouldn’t have bet on that if you’d seen her during her first trip to visit the Plainview, Texas campus. “Marsha Sharp (one of the assistant coaches then) had to come onto the plane to get me off,” she recalls. “But I got used to it real quick.”

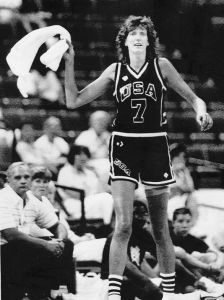

Wayland Baptist won two AIAW consolation bracket championships during Bush Roddy’s two years there. After graduation, Bush Roddy made the Pan American team that won a gold medal in Mexico City in 1975. She started every game along with Lusia Harris, Julie Simpson, and Anne Meyers. Other members of the team were Pat Summitt, Nancy Lieberman and Sue Rocjewicz. Averaging 87 points per game and allowing opponents just over 52 points, the U.S. women went undefeated in the tournament. Against defending champion Brazil in the game for the gold, the U.S. won 74-55, ending a 12-year drought for the U.S. women in international play.

The following year, Bush Roddy was the last person cut when USA Basketball was assembling the 1976 Olympic team. Still, she has lots of great memories of international play, including an incident in Moscow when she literally stopped traffic after she’d decided to let one of her teammates braid her hair.

“I don’t think a lot of Russians had seen a black woman with braided hair. People were slowing down and stopping to look at me,” she recalls. “The KGB had to come and escort me back to where we were staying. Nobody was mean or anything, but I was scared. Needless to say, I unbraided my hair as quickly as possible.”

Bush Roddy played three seasons in the Women’s Professional Basketball League (WPBL) with the Dallas Diamonds from 1979-1981. By then she was married to her husband Steve, doing coaching clinics with Clemson’s Jim Davis and Tennessee’s Pat Summitt, and working at one of the government plants in Oak Ridge, TN. When Coach Dean Weese (who’d been her coach at Wayland Baptist) called to ask if she’d play for Dallas, she asked Steve how he’d feel about making the move.

“All he said was ‘When do we leave’,” Bush Roddy recalls. “He’s always supported me in everything that I do.”

Bush Roddy attributes much of her success to her faith in God. It’s a faith instilled in her by her grandmother long ago and affirmed three years ago when she and Steve both survived battles with cancer.

“I never cried or worried,” Bush Roddy recalls. “I just gave God the glory.”

Three years later, they are both cancer free.

Carolyn Bush Roddy, holding city proclamation making Feb. 5 Carolyn Bush Roddy Day in her hometown. She is flanked by her husband, Steve Roddy (at left) and her son Brent Roddy. Carolyn Slay photo

Over the years, Bush Roddy has stayed involved in women’s basketball. In 1996, Bush Roddy became the assistant coach of the women’s basketballl team at Roane State Community College. A year later, she took over as Head Coach at her alma mater, Hiwassee College. From 2000-2003, she was Head Coach at Knoxville College. From 2002 through 2006, she served on the Board of Directors for the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame.

Bush Roddy has reservations about some of the changes in the women’s game. She thinks the 3-point shot is ruining the game. She thinks shooters should use the backboard more, and she believes parents shouldn’t let their kids play one sport all year round.

“I’ve seen so many kids who could have been great burn out,” she says. “Even though I worked hard, I was allowed to grow up as a kid.”

Bush Roddy is already working on her speech for her June 8 induction. She’s going into the hall with a group that includes Ticha Penichiero, Ruth Riley, and Valerie Still. She plans to mention some of the women who’ve gone before her, thanking them for paving the way for her.

“Players like Nera White, Dixie Woodhall, Pat Summitt…they’ve allowed us to stand on their shoulders to help build the women’s game,” she says. “I hope someday that some young women will say they stood on my shoulders too.”